In Sweden, internal passports were used for many hundred years. The oldest document stating the existence of passports (then called "our letter") actually dates as far back as 1279, when "our letter" had to be carried by men serving the king. With this letter they had the legal right to demand food and lodging for the night when travelling on errands of the king.

In the 16th century the word "pass" (passport) was used for the first time. The people now being controlled were primarily merchants. But soon after that, when the statesman Axel Oxenstierna in 1634 laid the foundations for the modern central administrative structure of the state, it became possible for the ruler of the country to actually control the travels of every single citizen.

In Axel Oxenstierna's structure counties were created, and the head of every county – landshövdingen – was directly responsible for carrying out the king's orders. Simply put, he was the king's stand-in in the county over which he ruled.

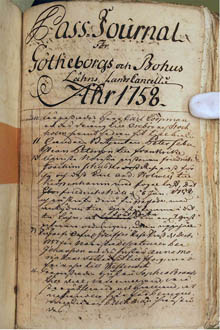

The administration grew and also needed some time to become really efficient. From the end of the 17th century and the beginning of the 18th century this growing bureaucratic efficiency did leave its traces! Here and there in swedich archives we can today find documents from this period mirroring how well (or poorly!) the passport administration was functioning.

The largest bulk of passport documents that has been saved dates from the period 1812 -1860. In 1812 there was political instability in Europe, a situation that triggered the state to inflict on its people the strictest rules for internal passports that the country had ever seen.

After almost fifty years of peace, and during a time when travelling and communication increased tremendously, the need to control where and when people travelled, and even to forbid them to do so, diminished. A vicar and member of parliament spoke in the Swedish parliament in 1858 and stated that he had travelled about in Sweden, Norway, and Denmark without even one official asking to see his passport. Only two years later the parliament, on September 21st 1860, voted for that passports were no longer a requirement for travelling. One amazing fact is that this decision not only applied to internal but also to international passports! This meant that people emigrating from Sweden did not need passports to do so. To find our ancesters who emigrated to the U.S. after this date we use passenger lists, the records of Ellis Island, and other sources, but not lists of Swedish passports. However, if someone was travelling to a country that demanded a passport for entering, of course a passport could be issued on request.

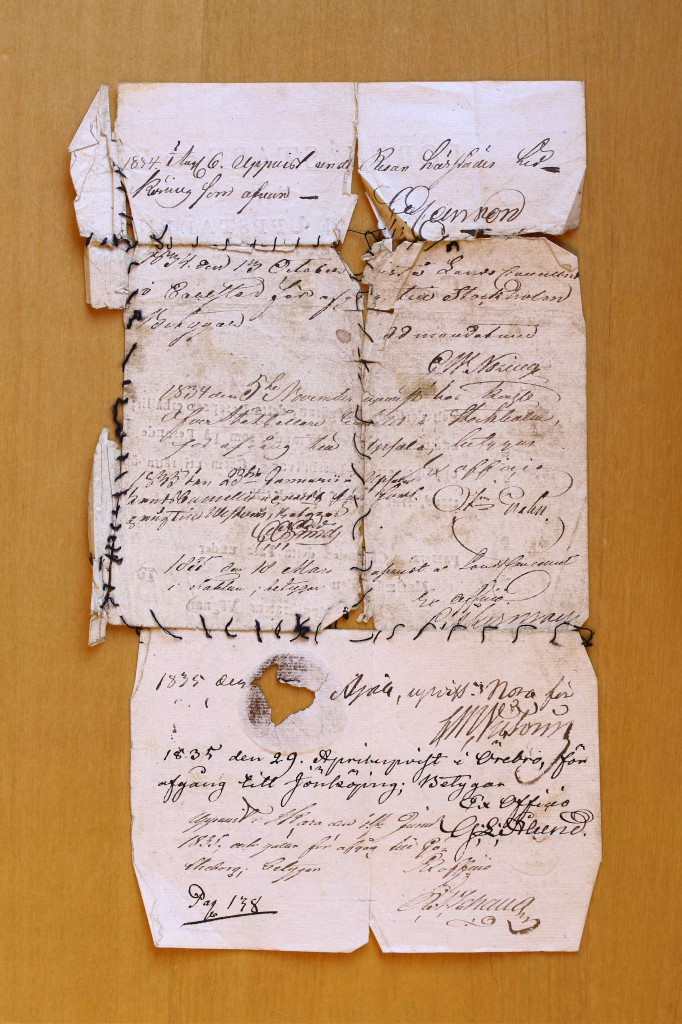

The picture shows page two of a passport that belonged to the tailor's apprentice Carl Lundberg, and that was issued by the mayor of Mariestad (in western Sweden) in the year 1834.

The documents that have been saved in our archives are interesting for a number of reasons. It's quite clear that this was seen solely as "working material" and that the documents many times were sorted out to be thrown away at one point or another. The ones that have been saved are many times unfortunately in bad shape. Still, there are quite a number of documents left to work with regarding internal passports. For the genealogist one tricky but also fascinating aspect is that finding your relative in this material is worse than looking for a needle in a haystack! However – today we have the internet and we have the possibility to actually register every single person we find in these documents.

In 2010 The Genealogical Society of Sweden (Genealogiska Föreningen or GF) initiated a long-running project to do just that. The goal is to register all people we can find in this fascinating material.

What documents have been saved?

First we think of the passport itself. Well, they were carried around by the person travelling, and so we cannot expect to find a large number of them, even though some were handed in when a person reached his or her destination or when the passport was worn-out (such as the one in the picture above). Today, some actually are found hidden or forgotten in family chests in people's houses.

First we think of the passport itself. Well, they were carried around by the person travelling, and so we cannot expect to find a large number of them, even though some were handed in when a person reached his or her destination or when the passport was worn-out (such as the one in the picture above). Today, some actually are found hidden or forgotten in family chests in people's houses.

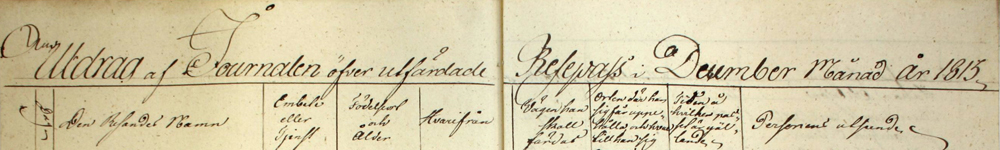

Lists – "passjournaler" – were created when passports were issued. Many of them have been saved and every page contains valuable information on a number of people. In the project these are the first priority to digitalize. As soon as the digitalized pages appear on GFs website we have people that start working on them, building up the records that we can search in and hopefully find our relatives.

Swedish citizens emigrating

Many swedish people who left for the United States before 1860 can hopefully be found in this material. Today we have a record containing almost 200,000 names, at this moment 222 of these state the destination "Amerika" (or "America"). The period that has been our main focus so far is 1812-1860. A large number of people in the early part of that period (approx. 1813-1816) have been registred, and as our work progresses we move forward through time. Please see the bottom graph on this page for amount of registrations for each year.

American citizens visiting

There were also american citizens visiting Sweden. If you do a search for people with "Amerika" as their home (hemort) you find over 140 americans. The number of U.S. citizens in the material however is most certainly larger, as not everyone had a note made of where they came from.

Quite a number of the U.S. visitors were sailors. As they arrived at one Swedish port and then travelled on, they would receive a Swedish passport, either for the trip to another Swedish port or to a port abroad. On January 8th, 1813, sailor Samuel Francis was issued a passport from Gothenburg to Copenhagen. We know very little about him, but we know he was 24 years old at the time (i.e. born around 1789) and Afro American. Every person travelling that did not have a business or an employment were described in their looks, usually age, hair color, eye color and height. Samuel Francis is described simply with the Swedish word for negroe – "neger."

We also find U.S. citizens working with merchandise in these lists. On July 17th, 1813, an American merchants assistant Stephen Field received a passport for travelling from Gothenburg to America. It was documented that he was 40 years old at the time, i.e. possibly born in 1773, that he had dark hair, blue eyes, and a body of "ordinary" build. On the same date we find Mr. Robert Peele, possibly a friend or business colleague, also destined for America. Mr. Peele was seven years older than Stephen Field, i.e. born around 1766, and has the same description of his looks as Stephen Field.

A piece of American history reflected in the passport lists

Yes, indeed, we find high and low in these lists. Everyone travelling had to have a passport. Even a minister who later became a U.S. president. The peace treaty to end the war between Canada (Britain) and the U.S. was signed in Ghent in December 1814 by five U.S. ministers and diplomats that had negotiated and eventually signed the treaty – John Quincy Adams, James A. Bayard Sr., Henry Clay, Albert Gallatin, and Jonathan Russel.

In this painting by Amédée Forestier we see the five American delegates. Adams is shaking hands, on his right-hand side we see Gallatin, Hughes (the secretary), Bayard, Clay, and Russell (one of the men on the far right is an unidentified person).

In The Papers of Henry Clay, volume 1, some interesting information about these negotiations are to be found. An early plan was actually to hold the negotiations in Gothenburg, Sweden. For this, Clay and Russell arrived in Gothenburg on April 14th, 1814.

Jonathan Russell was the U.S. ambassador to Sweden in Stockholm during the years 1814-1818. On April 18, 1814, he was issued a passport for a trip from Gothenburg to Stockholm. Joining him on his trip was "Mr. Lawrence and Mr. Russell as well as servants."

In a letter written by James Bayard in London on April 22nd he writes that the negotiations now were relocated to a city in Holland.

On April 23rd Henry Clay was issued a passport in Gothenburg for a trip up the Göta älv (river) to the city of Trollhättan, approximately 76 kilometers northeast of Gothenburg: "His Excellency The United American States Minister Plenipotontiatire at the Peace Congress here with Great Britain Mr. Henry Clay with servants to Trollhättan and back."

On June 2nd, Henry Clay was issued a passport in Gothenburg for travelling with a servant over Denmark to Holland.

John Quincy Adams had been the first U.S. ambassador in Russia, placed in St. Petersburg. When leaving Russia he travelled over Stockholm and Gothenburg. He first appears in the passport lists in Gothenburg on June 9th when the Swedish 19-year-old servant Nils Ericsson, who followed him from Stockholm to Gothenburg, was issued a passport for his trip back to Stockholm. "Servant Nils Ericsson, that has come here with the American Minister John Quincy Adams, back to Stockholm."

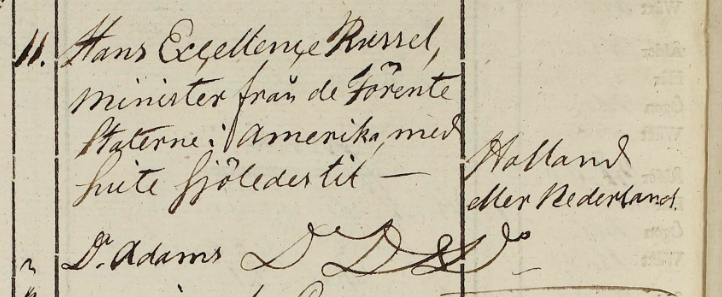

On June 11th, passports were issued in Gothenburg for both Russell and Adams for travelling to Holland.

"[June] 11. His Excellency Russel, Minister from the United States of America, with Suite by sea to – Holland or the Netherlands."

The negotiations in Ghent began in August 1814.

The future of the passport project

To digitalize the Swedish passport documents and also index all the names is a huge project. Jokingly we have said it will probably not take more than 90 years or so. Still, every month new interesting passport holders are being added and new searches can be made in the material.

Please feel free to contact the group working with this at the email address inrikespass@genealogi.net. If you want more extensive research done on this material, please contact our research services. Just klick on "Roots in Sweden?" on the right-hand side of our web page.

/ Hans Hanner, August 6, 2017, with assistance of Christopher Olsson